Kaijern Koo

Serious Things (2023)

There exists a duality to the word performance that feels both paradoxical and yet so logical. It is the understanding that it can refer to the actioning of a task, as well as a presentation; it can refer to the engagement with a duty, as well as a poetic expression before an audience. Think of the sore and callous Performance Indicators utilised by so many employers, hand in hand with the emphatic, soulful performance of a symphony. To perform can be to carry out a task, often begrudgingly, often for the sake of survival. To perform can, too, be an act of total passion and desire; an enactment potentially unnecessary to basic physiological needs. Perhaps it’s a little like the wolf parable – two creatures within one person fighting, respectively, for good and evil. The one that wins is the one you feed. So what does that nurturing represent when it comes to performance?

Mundane actions can be extraordinary performances, if you will them to be, if you indulge in the act. I once heard an alternative approach to one’s ‘day job’ as the fantasy of that employment being a dare – that one was simply pretending to be someone else during business hours – and, for completing the challenge, is rewarded approximately one billion dollars, paid in increments over the course of their life. Like kids in a trench coat, it turned the grind into a game. The rat race became an antic.

I got through my stint working in retail by turning it into theatre. Before the curtains parted for each shift, I painted my eyes in shiny colours and slipped into my little heels. My character called everyone ‘babe,’ tottering about the racks of sequined dresses, never failing to pout. The two wolves here become joviality and despondence. They feed on your willingness to participate, on your willingness to perform.

Any game relies on this same enthusiasm. Games, like most things, present an emulation of some aspect of existence. Scenarios of fantasy, chance, real estate, elite parties, and ornithology are contained to the span of a tabletop and delineated with goals and rules, kept alive by belief.[1] They turn the ordinary into theatre, where all cynicism is suspended. Meeples become puppets, held safely on a cardboard stage.[2] Any competitive tension brought about by the temporary seriousness is alleviated by the recognition that the game will end and one may fold it back into its boxy container. You laugh off any bitterness within your party and the catalyst is stowed away.

This is possible, of course, only with a mutual agreement of sportsmanship; the understanding that it was all an act, performed outside of reality. There is a dense buffet of horror stories recalling or imagining situations in which this very agreement is violated. The film franchise Saw or the more recent Squid Game serve as ready examples.[3] When the stakes rise past that which one has conceded to risk, hell follows. In less dramatic, more gruelling situations, resentment ensues if the comic relief fails to arrive to cut through the contention. These situations can be gamified, if you decide to see the strings, the edges of the stage. Games can reduce the tedium and lay them, contained, within neat and escapable parameters. They can make silly what you might believe is grave, for as long as you feed the right wolf.

If games offer the chance to pretend to be other, to play a part in a scaled-down world, the baroque spills across the bo(a)rders to transfigure whole landscapes into fantasy.

The two wolves are ultimately keepers of perspective. One may choose to view the world as either a chore or a game, and then perform accordingly, imposing that perspective on their situ. As games turn actions into acts, the baroque turns all of reality into theatre.

The Baroque period gorged itself on the dramatic. While games enclose theatricality to play out on scaled-down sets, figures of the Baroque turned ‘all the world [into] a stage.’[4] This plummeted out from the notion that “Things are nothing more than how they are taken.”[5] Reality is nothing more than what you want it to be. You are nothing more than the way you present yourself. They fed the delighted wolf to a state of delirium and, for a while, everything had the potential to be anything.

You could, like the so-called Sun King, Louis XIV, turn every aspect of your daily life into a performance, and have an audience standing waiting at the foot of your ornate bed in anticipation for the spectacle of your rising. In a moment where flux and uncertainty were inescapable, and the world itself seemed not to possess any innate laws, the only option was to adapt “an adequate mode of behaviour” – to play the game, even if you couldn’t see the rules.[6] Maybe because the despondent wolf seemed to be pulling all the strings, and because the rulebook didn’t actually exist, one could only fold oneself into a mad and dedicated act, building up a suitable character as if in an RPG, and painting heavenly scenes across every plaster surface like the manufactured endings to a game which was otherwise impossible to demarcate.

It gets a little slippery here, as the neatness of the wolf parable begins to falter. How very baroque, to be oozing out of the frames in which we wish to hang them. The metaphor works for games because they stay contained. The baroque is stubborn in its insistence on swelling and shrinking and forever shifting. It expands and contracts and tricks you with its rendered shine and illusory architecture. It is bound irrevocably to its context; not existing outside of reality as a game is, but instead splayed all across it. It makes theatre for an audience that is always changing, in a hall which glitters and flairs and refuses to stay still. Who might ever agree wholeheartedly to participate in such a performance? The costume changes seem never ending. The scripts roll on far beyond the point of conceivable memorisation. It sounds far too familiar for my liking – but, oh, did you see all of those jewels?

— Kaijern Koo, 2023

1 These examples have been chosen for the sake of simplicity. The same theory can, perhaps more loosely, apply to games which expand past domestic surfaces and into verbal interactions, screens, grassy fields…

2 “Meeples” refer, in board game lingo, to the small figurines which represent each player on a board.

3 This is explored in the brilliant podcast Weird Studies, episode 117: Time is a Child at Play; on the Mystery of Games, hosted by Phil Ford and J.F. Martel. March 2nd, 2022.

4 Shakespeare, William. 1623. “As You Like It.” In Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Tragedies, & Histories. England: Edward Blount and William and Isaac Jaggard.

5 Maravall, Jose Antonio. 1986. Culture of the Baroque; Analysis of a Historical Structure. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 195.

6 Maravall, 1986. 190.

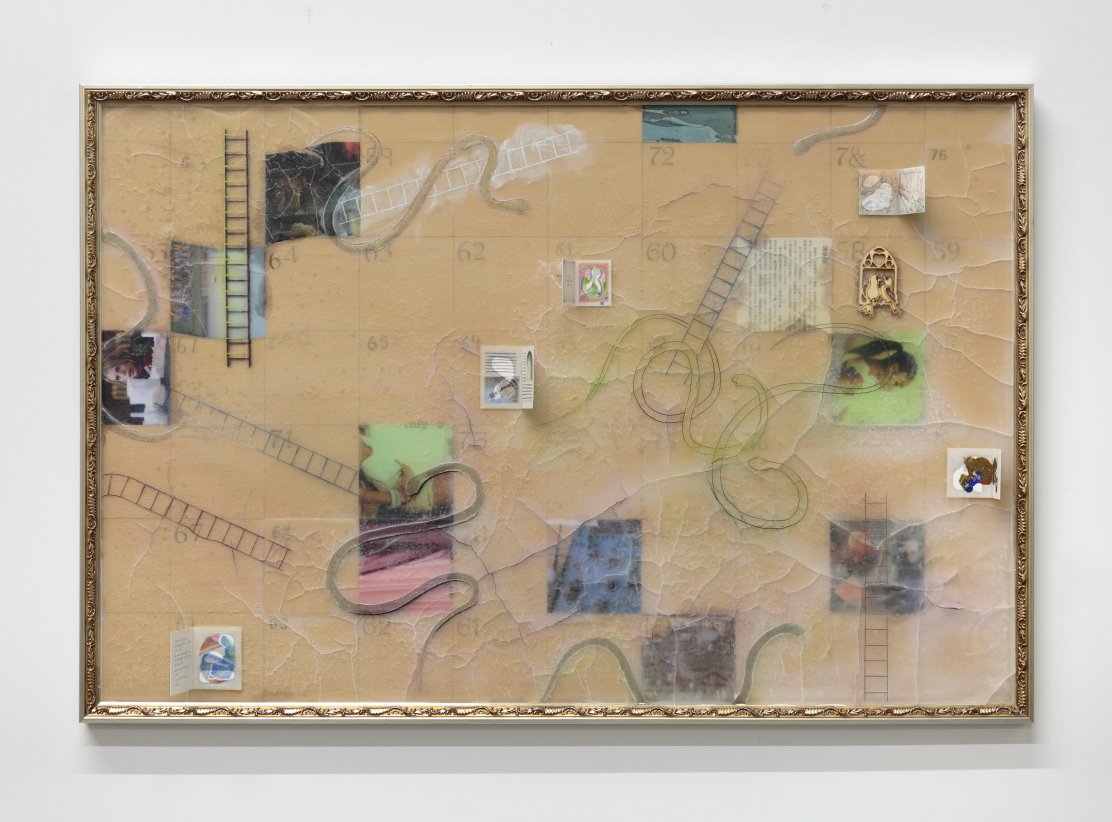

Kaijern Koo, that ain’t plot (2), 2023

paraffin wax, paper, resin, glitter, found images, pencil, oil paint, ornate frame

60 x 90 cm

photograph: Tim Gresham