Romily Plourde Marbrook

’Swap/Meet’

CATALOGUE ESSAY FOR MATT ARBUCKLE’S THE PUNCH

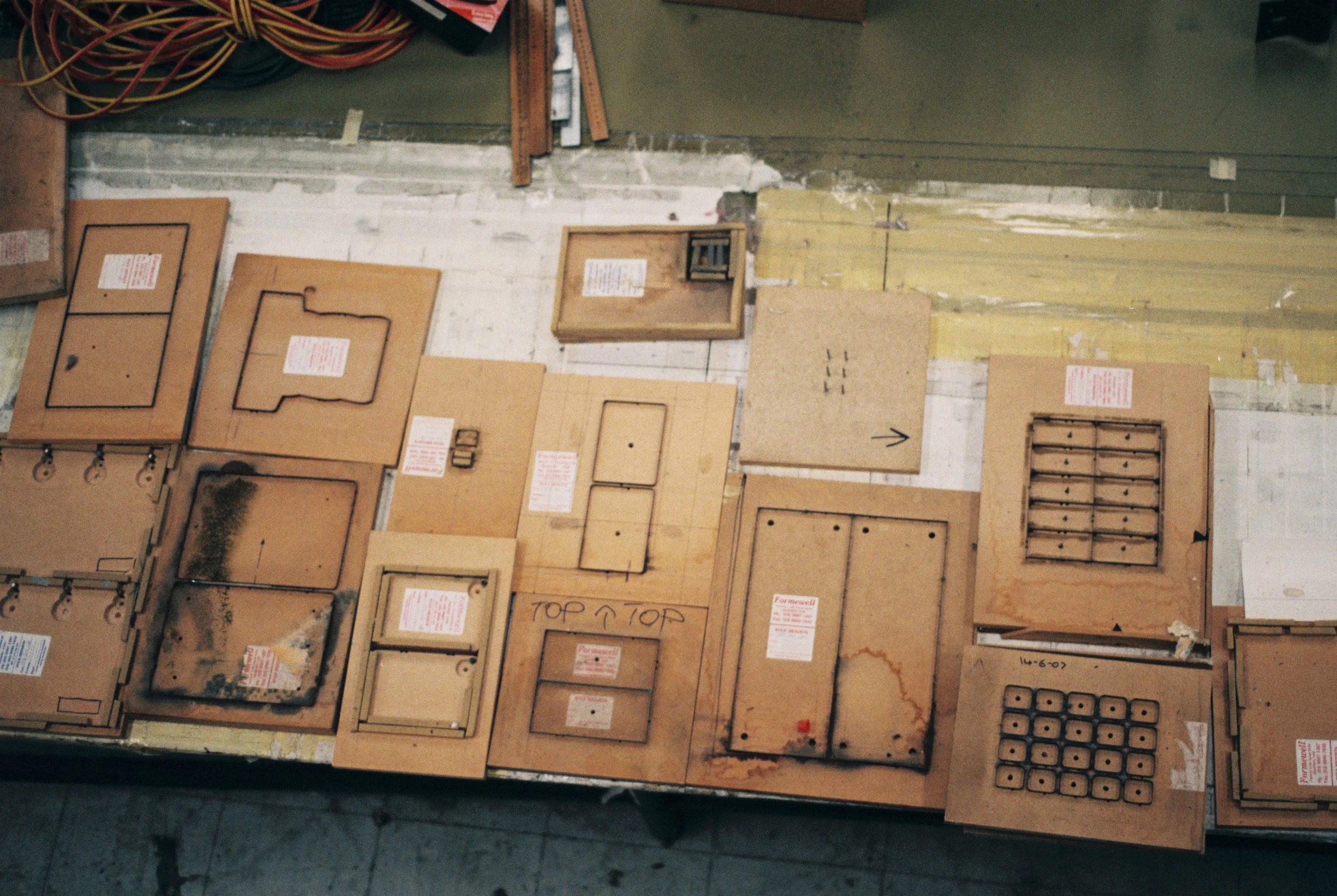

The Punch (2019–2025) is a series of paintings by Matt Arbuckle created on supports of industrial wooden fabric guillotine blocks. The blocks are covered in thick layers of acrylic paint, haloing the ghosts of the shapes they once cut; the paint seals in dust and peeling wood, and glazes over logos scattered amongst the blocks. What emerges is a mysterious assembly of forms—shapes that we attempt to give meaning to: yin-yang patterns, geometric assortments of triangles and cubes. A dialogue is created between the origins of the items in the Justincraft Textile Factory, Matt’s practice and penchant for salvaging forgotten objects, and the journey in between.

Without knowing the origins of the supports, the objects are formally abstract. They are evocative of a Montessori classroom; the shapes and primary colours painted on the cutting die resemble building blocks of various shapes and sizes, with the tell-tale signs of age and use visible. They remind me of doors, drawers, or portals. The supports are, in a way, portals to the Naarm textile factory they originated from. In a message to Matt, “G”, proprietor and historian of the since-closed Justincraft, describes the process of using the blocks as “...brutal and unforgiving. Mistakes are punished. Though a repetitive task, it was one that required extreme vigilance.” The punishing repetition of manual labour is condemned to eternal life through the hardiness of the acrylic paint, which seals in the impressions made by workers—the corrugated edges, shapes, and symmetry of the grid: accuracy and perfection.

Justincraft Textile Factory, photograph: Matt Arbuckle

The works as a group are a kind of bricolage—the creation of something from various things. In his historical account, G explains that the purpose of the blocks was to create fabric swatches: “The retailers would show you a thing. We made that thing.” The omniscient thing, both trash and treasure. The past life of the surfaces is gently reminisced on to honour G, Justincraft, and his family and employees who laboured over the blocks—the many hands that brushed over them, repositioning, packing, cutting, punching, and then coming back the next day to do it all over again. G recounts, “People knew that their work was valued... the nature of the work meant they could see tangible results... they made friendships, they established families, became part of the fabric of society... At the end of the day, you can admire your work, put it in a box and send it out the door. Next day, hopefully a new task awaits you.”

Matt exhibits at the gallery where I work, in Tāmaki Makaurau. He will frequently arrive with bric-a-brac he has found on the side of the road—items he is selling, has bought for an astonishing deal on Marketplace, or some obscure item of unknown origin he will try to offload on us. He tells me that on walks with his son, he will boost him up when they pass a skip to scout for exciting objects inside. Matt traffics in found objects, his studio a kind of backwater historical museum of forgotten things—odes to trade, history, and chance meetings. Objects collected over years: an ancient cataloguing system used at the Art Gallery, marble offcuts, ornate cheeseboards, dollar scratchies—all filled with potentiality.

I asked Matt if he thought any of the objects he found could be haunted, as I’d immediately begun to think about hauntology due to my art school indoctrination. He replied, “I don’t. I do think of the history—who could have used this thing? Getting to meet the previous owner of an object can be just as interesting as the object itself. More often than not you can swap stories and learn snippets of them or their family. The story of life is wrapped in one’s day-to-day existence.” This is a more life-affirming way to look at it. A trip to purchase an item from someone’s home will lead you on a journey to a suburb you would have never visited. More often than not, it leads to a surreal and personal conversation with someone you would have otherwise never crossed paths with, breaking out of your daily routine and routes. I see it as goal-based flâneurism, or a laissez-faire ethnography. Practice and methodology are brought outside of the studio, beyond spaces typically confined to art-making, and intersect with the wider community, family, and strangers—and in this instance, somehow resulting in G’s story being told through the tools he once used.

Justincraft Textile Factory, photograph: Matt Arbuckle

The path that led Matt to the blocks loops back to his practice using voile, which has been his primary support in recent years. He happened across the blocks whilst visiting Justincraft as they were closing down, being given free rein to go through the rolls of fabric that were left behind. The objects initially caught his interest as formal arrangements or abstractions, but after understanding their use and history from G, they began to hold a narrative through their process and story. Both his use of voile and the blocks in The Punch involve the same methodical process, which opens itself up to chance—alchemical reactions of pigment and the earth in which the voile is buried to cure. The chance and the reaction leave behind traces: grass clippings, sawdust, maybe a stray anonymous hair.

In between jobs, I once worked in an electronics warehouse as a pick-packer. At the time, I considered it “blue collar” because we had to wear steel-capped boots and high-vis vests, and there was dust and dirt everywhere. It was one of my favourite jobs. Half of the workforce were my friends, and the other half were devout Anglican youths, which created a wonderful point of difference. Because our everyday tasks could have been described as “mundane,” we had possibilities and freedoms to create friendships and elaborate jokes, swap stories, and define ourselves outside of the partitions of the warehouse. The input was clear, and the output was evident when a postal delegate would arrive daily to clear out the mountain of packages we accumulated throughout the day.

The Punch also recalls the phrase “punching the card,” a now-antiquated method of tracking an employee’s total hours worked—or an expression signifying the end of a working day, or death. The action of punching the time card is much the same as using the fabric guillotine: a swift and decisive action. Both proudly declare their origins in factory work, with traces of unionisation, smoke breaks, and the sweet relief of leaving your obligations at the door when you punch out.

Work of this flavour is edging towards extinction, with automation and offshore outsourcing becoming the norm. Every week, a new story emerges of a factory closing or being sold, another regional livelihood lost, and more objects permeated with significance set to be auctioned off or driven to the tip. The simplicity of the gesture of the paint on Matt’s supports preserves and celebrates that significance. The bright primaries chosen to adorn the gridlines around and within the blocks could be interpreted as windows into those moments of community and joy found within the repetition—or found later on in the “free” section of Facebook Marketplace. After all, at the end of the day, you go home, and the next day, hopefully a new task will await you.

— Romily Plourde Marbrook, 2025

Studio view, photograph: Matt Arbuckle