John KINSELLA

‘ON THE PHOTO-PICTURE DIPTYCH-MAKING OF ZOË CROGGON: CONTESTING DUALISM’

CATALOGUE ESSAY FOR ZOË CROGGON’S ASLEEP ON WATCH

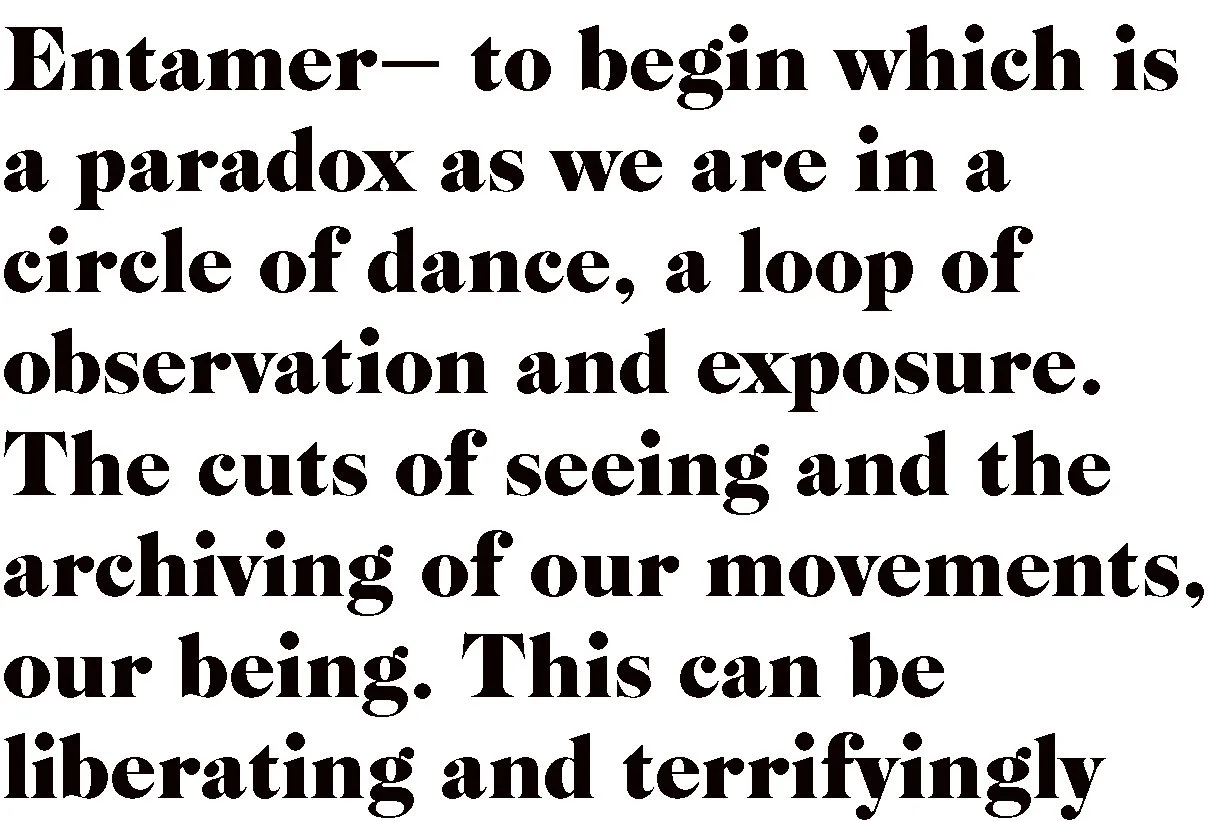

Zoë Croggon

Origami, 2025

screenprint on aluminium (unique print)

Entamer — to begin which is a paradox as we are in a circle of dance, a loop of observation and exposure. The cuts of seeing and the archiving of our movements, our being. This can be liberating and terrifyingly invasive. Zoë Croggon’s diptychs of juxtaposition and transition, of dialogue and transposition, take us to an essence of being, but also question the maps we take to a spatiality expecting to find our way. The correlations presented here between dance and form, between choreography and mimicry, between shape and language (silent, suggested, urged), move across cultural spaces with respect, without appropriation, but also with a deep fascination about why we read sensual presentations in overlapping ways for all our probable difference in experience and culturality. This is an exhibition about viewing and messages — about how we interpret signals both in their presented, predictive modes and through the hidden, their allusions to a state of planetary vulnerability.

‘Origami’ is a continuance across the diptych panel divide. I think of the use of staples in a chapbook by Cambridge poet JH Prynne working, in a way, as colons that we might read across. The natural descent of the flipping acrobat, dancer. The Muybridge like experiment in observing movement. The first plate of the ‘person’ that has been set as plaster, with human tissue and clothing intact as ‘real’, but made into a form as if by metamorphosis. Already in that one image we have the human becoming non-human and vice versa, the life in the movement and the question of what will become of that caught/stilled movement. We cross and descend to a paper fabrication... an approximation of the figure in the next stage of the lateral drift, of the displaced physics and physiology. With the nuances of shading against the darkness, the plaster-white paper, the bleached paper, becomes uncannily more human than the original figure — one and the same but almost in ways we might not expect. To shape the paper, to fold and bend, to make it enact, to mimic, but to hold its own latent energy, its own tensions. This is what I would call a de-mapping.

The great dance photographers Barbara Morgan and Louis Greenfield come to mind with shape, with form, but not in visualisation, but it’s the poetry of dance writer Edwin Denby that keeps permeating as I experience these remarkable diptychs. There is something of the ‘medium’ about Croggon’s interpretations of choreographed human movement — a scrying of the hidden, a delving into the motives behind presence. This is not to possess the image, but to contribute to its liberation. And it’s a complex analysis, because surveillance is an enforced choreography, a reading of what comes into the range of artificial senses with human senses awaiting outcomes. In ‘Wishbone’ we have the disturbance that is also fulfilment, and we have the human expression juxtaposed to its essence, its nomenclature — the curves that overlay and make up the map of embodiment. Both images are of the same ‘thing’: an act of pattern and elevation, of joie de vivre. They complement each other. But in the same way that ‘wishbone’ can refer to, say, a part of a sail (and these images both are at full sail), or part of a chicken’s anatomy with human superstition written into its human utility, the contradiction also works as a correspondence. The diptych makes for a poetic symbolism which taken in the context of the broader exhibition becomes social commentary. There’s a conversation between the two panels of ‘Wishbone’ that takes in early modernist liberations of body yoked with the correlations between body and mechanism. Maybe this is the biomechanics behind a Grace Cowley ‘inanimate object’ composition? And in the mirroring, we have the ‘looking glass’ syndrome of what exists on the other side being at odds with reality, and in that dysphoria an alternative map to presence, our presence in the image and as viewers of the image.

Zoë Croggon

V Formation, 2025

lithograph on Somerset Satin

‘V Formation’ is the rejoinder to the confidences around ‘Victory’ celebrations. Behind every victory is unreadable ‘costs’. Again in the diptych’s juxtaposition, a continuance of shade and light, an apparently similar surface of flat (vertical, we assume) planes and sky. Completely different and yet at least demi-continuous. This is a rewriting of movement and stasis. The still life becomes life as pattern, in the pattern. Chevrons, sharp angles, acute statements. The pegged sheet of paper is the fold, the flap of an envelope. Wings are expressions out of paper and sculpture is co-ordination and performance. Imperfection of formation is the truth, a breaking out of the pattern to generate chaos, pattern, a language of fractals. Form. It is always laden with intent, but intent is not pegged outside the caught moment. In a way, the ‘Untitled’ lithograph with not-quite-quartered folded paper juxtaposed with an apparently ‘perfect’ corner of a room is an ars poetica, a manifesto of the imperfect nature of architectural and enscripted ‘perfection’. What the eye wants to see — how we want to follow a map as a truth when it’s a highly mediated arrangement of ‘things’ and ‘shapes’ in the world. There is no specific trick for the eye-brain to unravel here, but there is a statement about the way we enforce patterns of expectation.

I know writers and activists working in Georgia. I read ‘Ushba’ and I think of the snow-encrusted yet warming Caucasus Mountains. I think of the vulnerability of ‘permanence’, the tenuous nature of human interactions — between each other, with the natural world. I have seen many photographic representations of the mountain and its range, their profiles. That’s more often than not expressed in conventional topographic and geographical terms: the images, the descriptors. I know this is not the only way and Croggon’s ‘Ushba’ goes to the human interface — the inchoate representation of the choate, the shape as we might imitate and that we embody in our merging with other people. Again, a tension, but a constant move towards resolving that tension. A pas de deux that is so personal, so bound in the discovery of the terrain of body and surroundings, but also cosmological and geological. The bedrock of our existence, of the existence of ‘features in the landscape’. We are working outside conventional Western geographies and outside purely anatomical notions of the body. There are mergings, extensions — light, shade, crevices, exposure, walls, illusions and delusions. The ruptures and creases, the solidity and fragility of the most immense mountain range and the most ‘fragile’ human body. It’s all immense and increasing because it can’t be simply mapped or forced into the shapes of status and power. The anti-geography is an expression of an internal cartography that is infinitely complex.

The ’Altona Beach/Pine Gap (by Mick Tsikas)’ lithograph diptych is at the core of understanding the essential ‘message’ of this exhibition about messages. If we have the apparently benign but ‘moody’ image of Altona Beach, Naam, underpinning the ghostliness of the Joint Defence Facility Pine Gap a short way out from Mparntwe in central ‘Australia’, it is suppressed underpinning. Under that brooding sky, we get the feeling of intrusion, of surveillance, the spy satellites reading through the vapours, reaching under the reflections of the sea. If the visual power of each diptych comes from the movement of light in the black and white plays between each ‘panel’, this is especially emphasised in this piece. It’s collaborative, as it needs be — and it’s an ironic inversion of the so-called collaborative drive of the spy base between American intelligence agencies and Australian signals. The military, cryptological raison d’être of the base is reinforced through the false geography of ‘isolation’ (being on the sacred country of the Arrernte people, it is far from isolated to them), allowing decisions to be made through interpreting signals data and issuing orders that determine the fates of people at great distances but also by implication (and through occupation of country) close by. With its natural surroundings ‘snow’ effect, Mick Tsikas’ image emphasises the false ecology of the domes all the more by their ‘looking like’ the radar domes they are. Uncanny on one level, but also a representation against the absurdity and surrealism of their presence where they have no place. Again, to the juxtaposition — different country, different geographical features, coast as opposed to the deepest inland one might search out (to avoid signal capture from the ocean) — and yet, they are yoked together by the politics of surveillance, of power. Both images have the feel of nuclear annihilation.

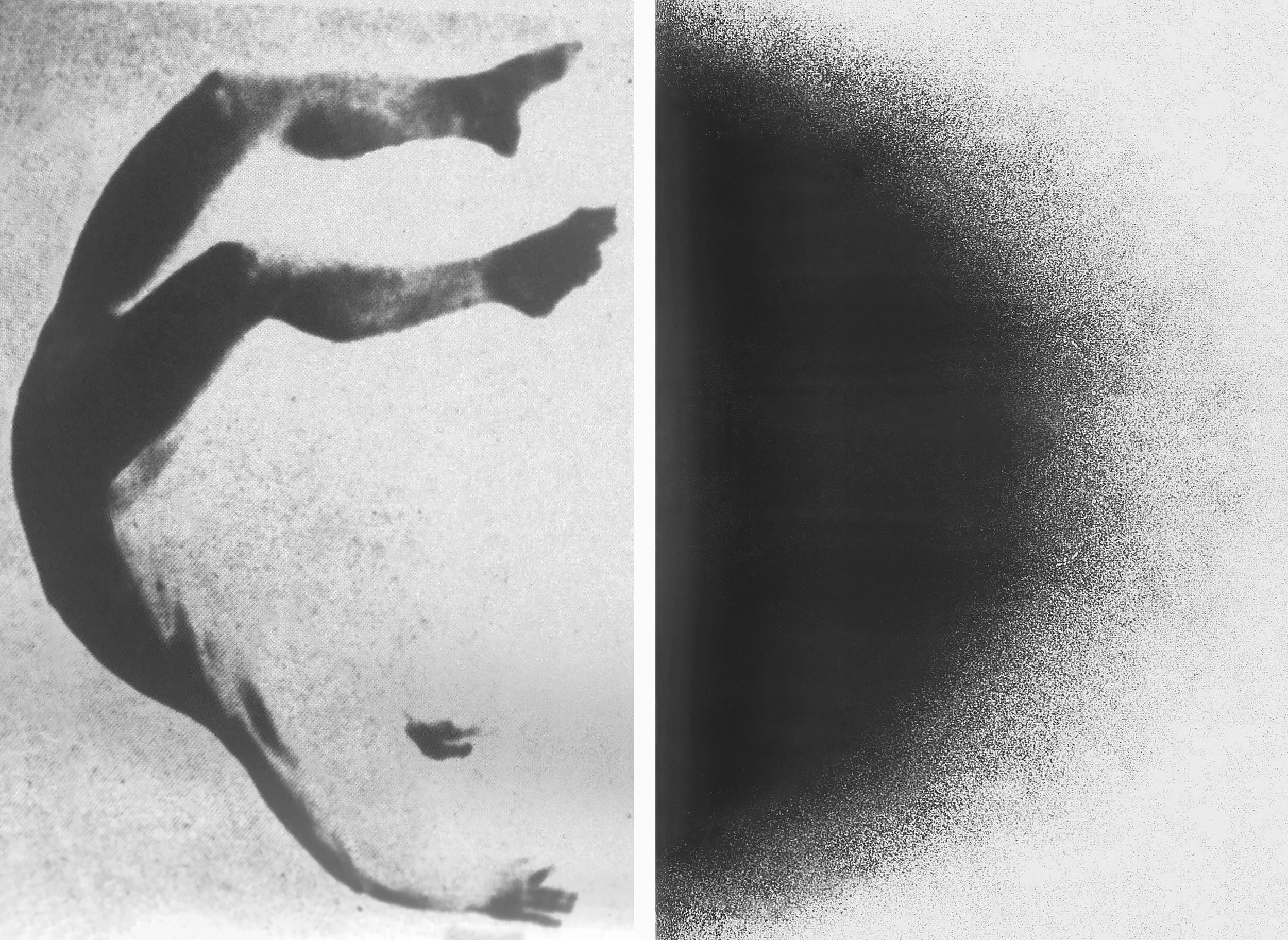

Zoë Croggon

Black Sun, 2025

screenprint on aluminium (unique print)

In the diptych ‘Black Sun’ the curving body both completes and creates the sphere of the solarised sun. The body is the source of life as well as the result of the source of life. I was strangely reminded of Edvard Munch’s ‘Dance of Life’, not because of a visual correlation, but a compelling mismatch — a false organicism that we find with all predictive geographies which Croggon seems to me to be opposing. Further, the athletic body is ironised in an anti-superman way: an inversion of the fascist symbolism of the ‘black sun’ through the ‘glare’ eroding the features/face/head and gradually eating into the curved figure which becomes desperate rather than consoled by the power of the sun. This anti-symbol/symbol relationship troubles us more than it placates or affirms. If we consider this diptych in the context of the Altona/Pine Gap diptych, we see both the manipulation of the body by symbols of power as well as the secretive quiet and diverting modes of power.

During the ’80s and ’90s, photographer Richard Woldendorp produced series on series of aerial photographs (pre-drone) that sought to show the wider significance of imposed patterns in ‘landscapes’. Topography becomes abstraction (with suggestive allusions to, say, the paintings of Fred Williams). Whether these images critique intrusion in the way I tend to perceive these things is up for debate, but what they did do was ‘reveal’ the effect distance and perspective have on perception when combined with our expectations and assumptions about what makes something an artwork. This highly Western way of consuming the visual and reshaping, say, colonial acts such as clearing land, ploughing and seeding vast crop monocultures, is brought into a potentially very different perspective in Croggon’s ‘Afterimage (barley, wheat, pistachio Crops). The aerial view of the mosaic of planting and controlling country for agriculture is there, but the juxtaposition with the ultrasound kneading hands (reflecting each other, doubled... and the hands taking precedent through being ‘first’) questions shape, origins, intent, and provision. The issue of cause and effect, of gestation and source, are worked into the question of intent. There’s no specific answer there — these are not didactic works — but within the broader context of the exhibition questions are being asked.

If Woldendorp insisted on a geography, Croggon questions the very reason for such a geography. The aerial image as de-surveillance. As with ‘Asleep on Watch’, the curled ‘sleeping’ figure will fall through the division between panels into an amniotic fluid, into a gestational sea of mixing fluids and dissolving/generative fluidity. Vulnerability but also ‘taken with the flow' of circumstances, events and impositions. It is calmly terrifying and deeply unsettling. The image is made and unmade in imagination but also within both the natural processes of the elemental and also as a consequence of intrusions of power. If paradoxes are made from contradiction in juxtaposition, disrupting any binary reading, so also do the images draw to each other in magnetic ways. ‘Blind Eye’ has us seeing into the folds of our sleep, our nightmares, our places of security with insecurity, doubt and also wonder. The co-ordinates are unpredictable, essentially unmappable though creased fabric is a guide to a liminal terrain. We will leave the exhibition unresolved and questioning our own assumptions, unsure of how the earth, fire, water and air we move on, around and through are mapping us rather than we them. That seems to me the purpose of these works singularly and taken together.

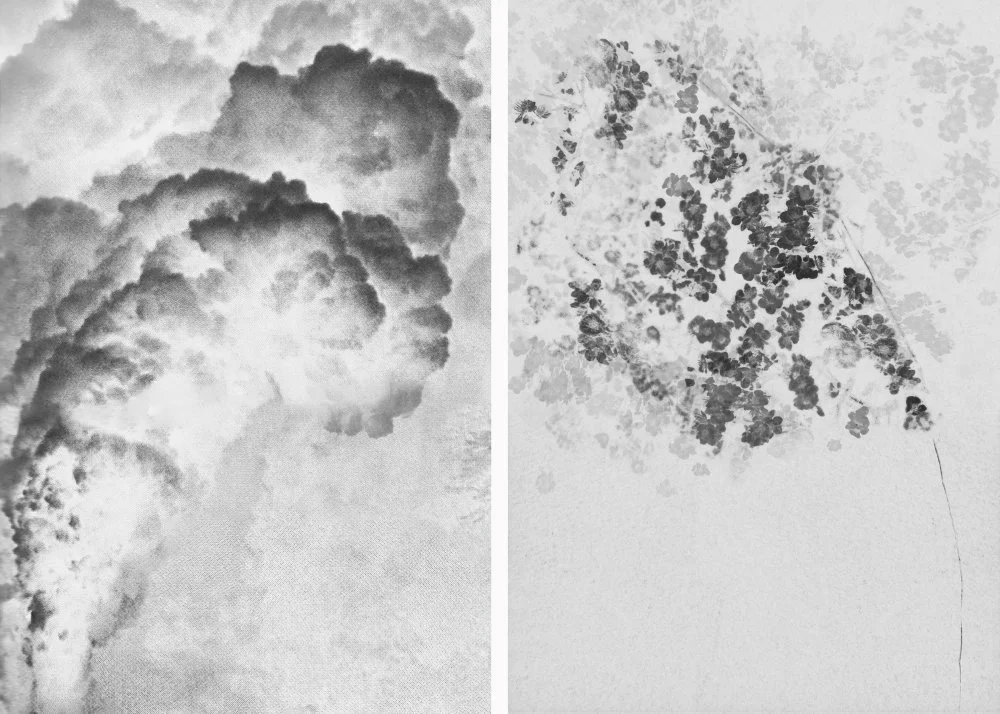

I will finish with a poem as response to ‘Bloom’ (screenprint on aluminium) which is the way I best know how to unprocess the processed. This is relevant to me personally because I campaign against the destruction of the Western Australian jarrah forests and aluminium in the consequence of bauxite mining. I call it a ‘false shine’ and Zoë Croggon’s ‘Bloom’ so beautifully expresses an irony of materials and similarity, of analogy and simile, and ultimately of metaphor’s place in visual art. The bloom on the left side of the brain of the diptych (perversely, the reasoning language side — capitalism knows its stuff) seems a toxic cloud of industrial exhaust, the artificial ‘clouds’ of a carbon-spewing smokestack (such toxicity often carries a sublime ‘beauty’), while on the right side of the brain (creativity... you know the drill) the delicate flower print that fades in and out of definition (with another sort of sublimity in its bold vulnerability). They bind towards each other in Rorschach test mimicry, with a deadly eschatological urgency... bent by the will to pattern and ‘completion’. This grim, pessimistic masterpiece of irony extends all the way (to my mind) to the ‘geographical’ and ‘geological’ source of the corruption: the industry that kills country and the biosphere. Croggon knows the costs of making art so will make that art work to contest the wrongs. A minimal impact for maximum correction is the desire. It’s a desire worth considering in all its implications.

BLOOM

after Zoë Croggon’s diptych

I urge towards your delicacy

with stains of ephemera; that

thick root stock of conversion,

those hairs and stamens, stigma

and stylus on the glimmer, sheen

dulling such brazen optimism.

I darkly polish a petalled sky, over-

whelming cloud & testing

satellite wonderment. Lean

towards me perfectly, brutally,

arch and touch my hot cheek

with a spray of resolve, of design.

John Kinsella is an Australian poet, novelist, critic, essayist and editor. His writing is strongly influenced by landscape.

Zoë Croggon

Bloom, 2025

screenprint on aluminium (unique print)